Guides

- Home

- Traveller guides

- Looking back on 40 years of Dublin Pride

Looking back on 40 years of Dublin Pride

Celebrating the 40th anniversary of the first Pride, activist and writer Tonie Walsh wrote this essay in 2023, looking back on the changes to Pride movement over the years.

This June, upwards of 60,000 people will participate in Dublin's LGBTQ+ Pride parade, making it one of the biggest in Europe and the single largest socio-cultural event in Ireland after the city’s St Patrick's Day parade. Community activists, NGOs and associations from civil society, statutory bodies and the defence forces led by the Army Band will join their LGBTQ+ brethern in an exuberant display of visibility, positivity and inclusiveness that was unthinkable thirty or forty years ago. And I will proudly be marching alongside them.

As people take to the streets and parties erupt across the city, there will also be many reminders that Pride has its roots in much smaller, more troubled events of the 1970s and 80s; events born of protest and trauma as much as pride.

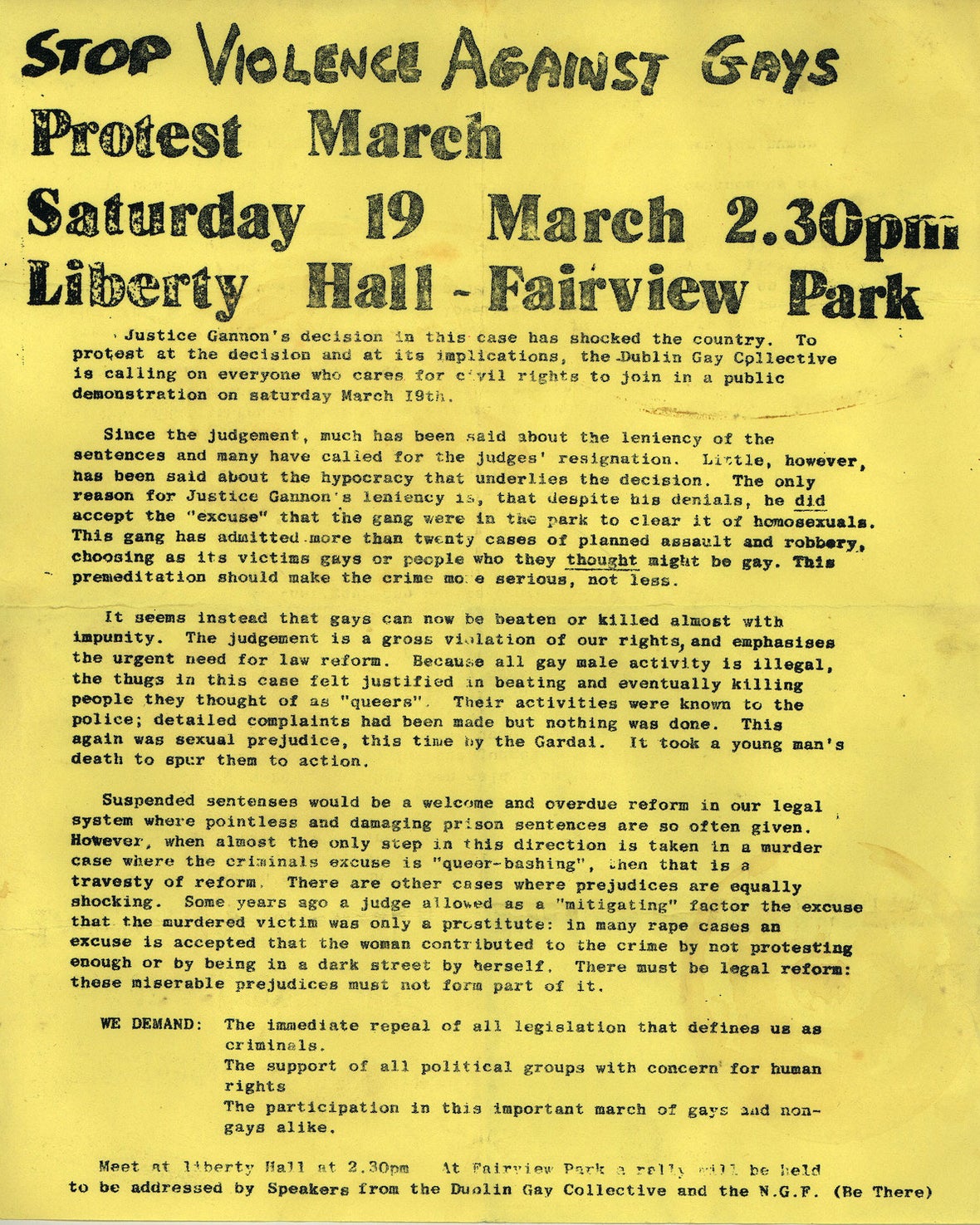

The birth of Irish Pride

In March 1983, when five youths walked free from court after fatally assaulting young Dubliner Declan Flynn, people’s anger and fear was funnelled into the largest LGBTQ+ demonstration Ireland had ever seen. Now known as the Fairview Park march, some 800 gay men and women and their allies walked from Liberty Hall to the scene of Declan’s brutal murder, protesting a culture that seemed indifferent to the violence that women and gay people routinely experienced. That march was a transformative moment and it would feed directly, three months later, into Ireland’s first, proper Pride march.

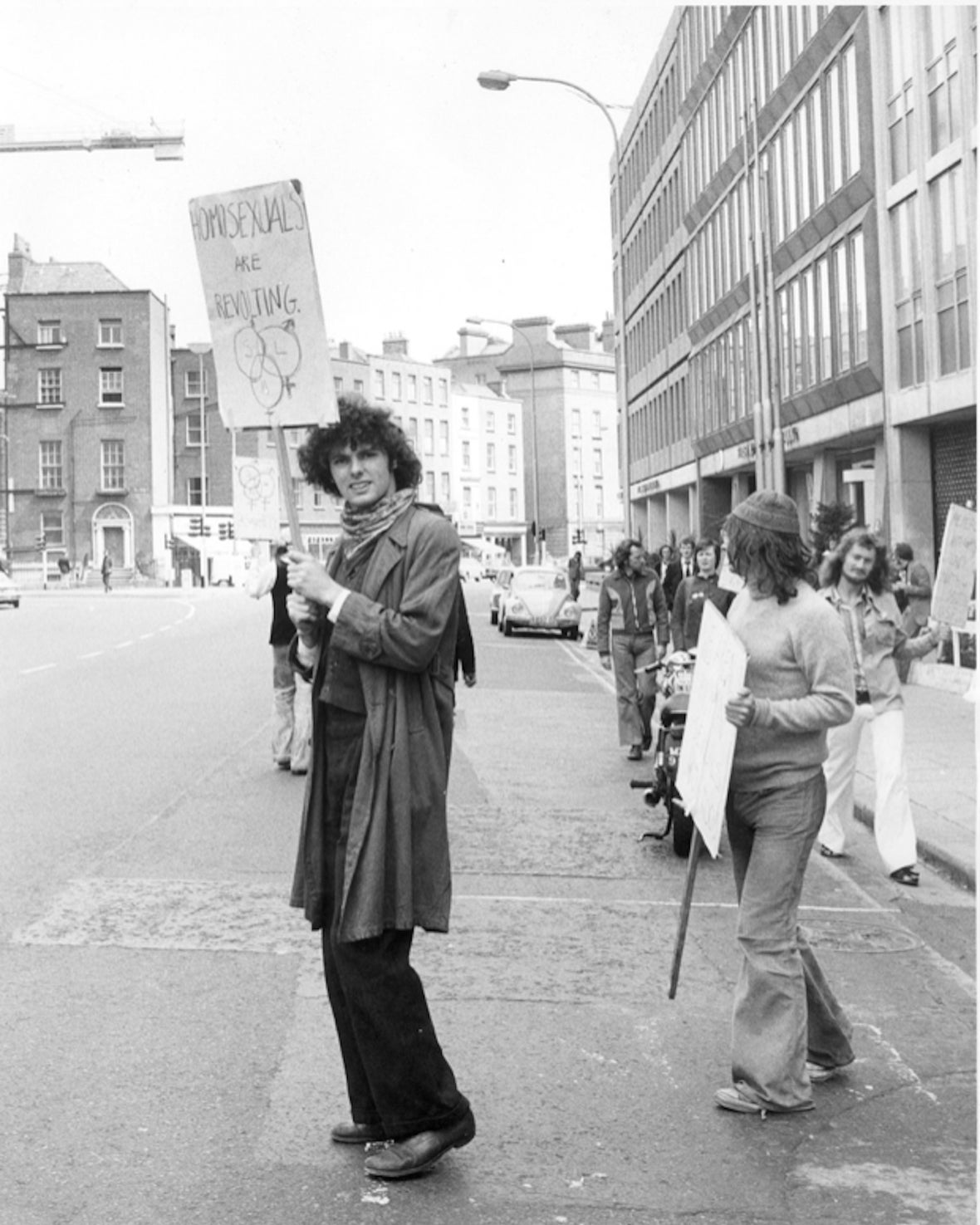

I call it a proper Pride march, but it wasn’t the first public expression of gay pride. In June 1974 a tiny group took to the streets to protest the existence of archaic Victorian legislation that criminalised any form of public or private intimacy between men. There were only 10, but included in that brave little group who picketed the British Embassy and the Department of Justice were Jeff Dudgeon and David Norris, who would later successfully sue the UK and Irish governments, respectively, over the offending anti-gay laws.

The LGBT civil rights movement (‘Q’ was still a very controversial term back then, and '+' wasn't even on the radar yet) was just six years old when I attended my first Gay Pride Week (as it was then known) in 1980. Still in its infancy, there weren’t the numbers to sustain a fully-fledged march or parade. Instead, the high point was a release of pink balloons in Dublin's city centre. Just over a dozen of us handed out leaflets explaining the history of New York’s Stonewall riots (when in 1969, that city’s gay community took to the streets in anger following police brutality), and asked people to wear a pink carnation as a sympathetic buttonhole.

At 19, full of the optimism and the anger of youth, I was on a mission to change the world. But I was also somewhat blind to the dangers that lurked on Dublin’s homophobic streets. Afternoon shoppers seemed bemused by our pink-hued revolutionary antics but I was left in no doubt about our states of exclusion when, at the Pride picnic the following day in Merrion Square, the park warden asked us to leave; forever a criminal, a social outcast.

The fight for decriminalisation

In later years, there would be guerilla-style zaps of various pubs in Dublin or Cork, with the express intention of highlighting those states of exclusion, at a time when it was legal to refuse someone service if they were lesbian or gay.

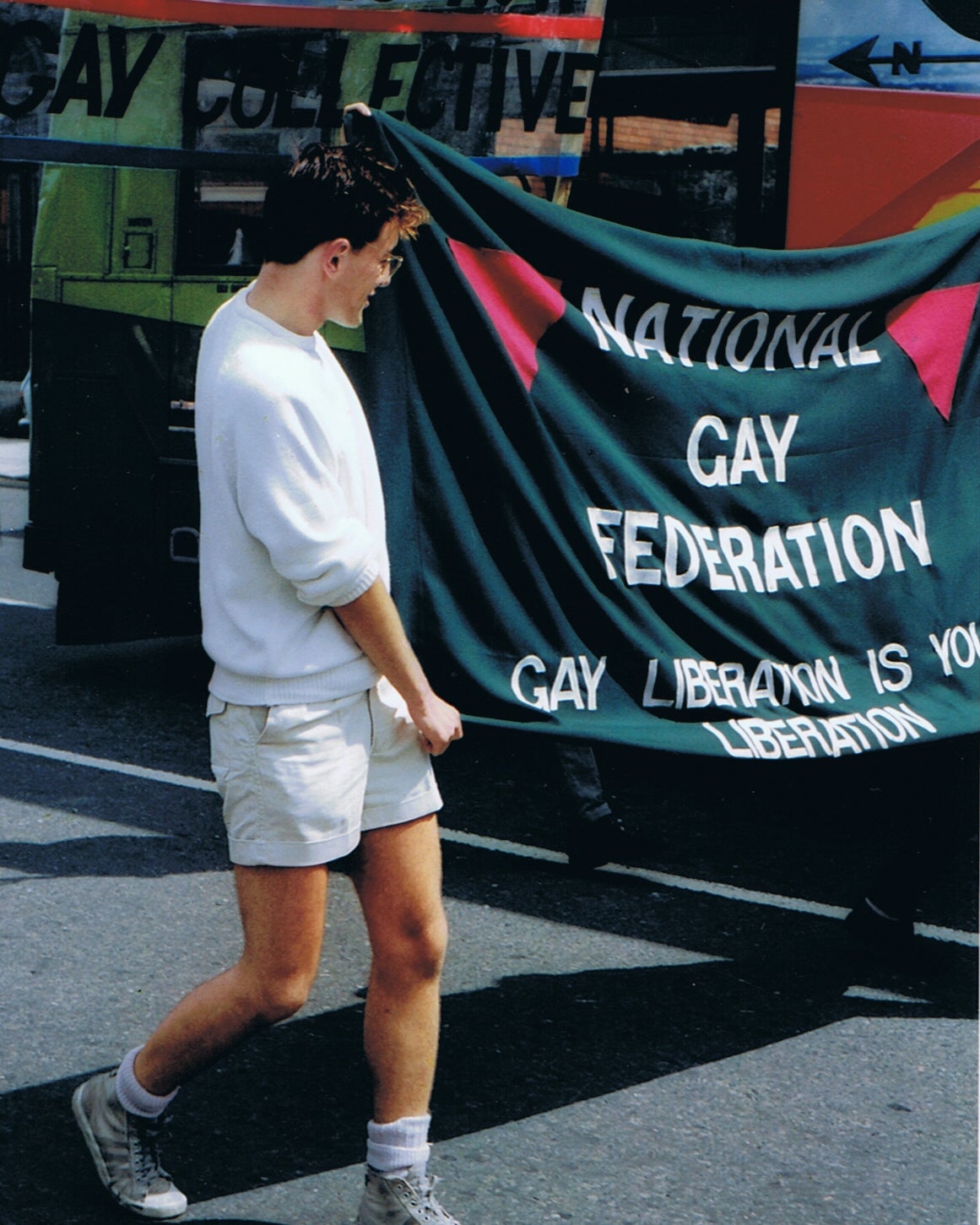

”Gay Liberation is Your Liberation” declared one of the banners on that first, proper LGBT Pride parade in June 1983. It was a bold statement of intent, generous in its sense of inclusivity. What is Pride if not a fabulous, glittering opportunity to share one’s queer world view with the rest of Irish society? And bring everyone along for the ride. To liberate all in one’s wake.

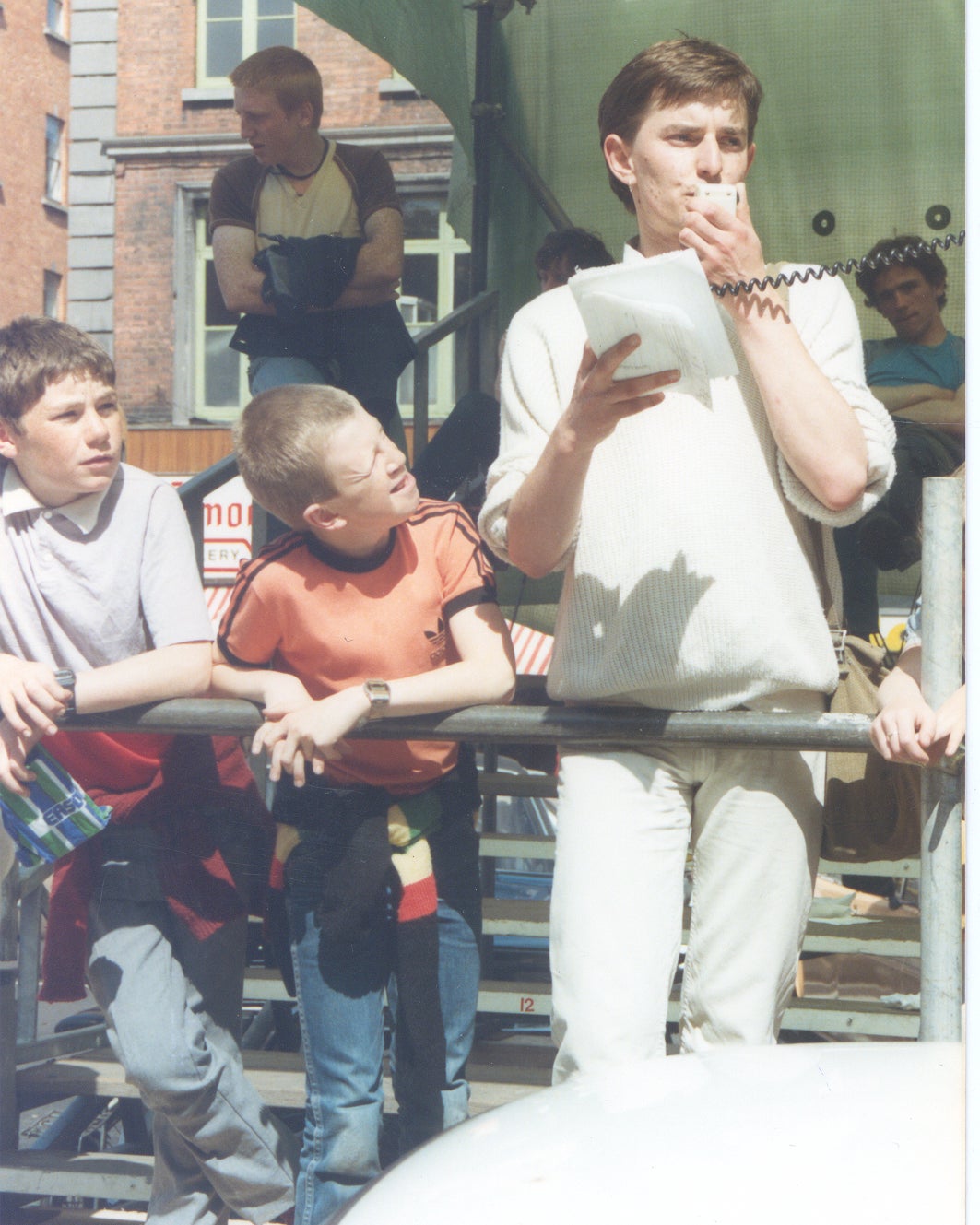

At that first parade, it really felt like we were protesting our pride. Tellingly, it was billed as the ‘Gay Rights Protest March’ with barely two hundred people, drawn from every large city on the island of Ireland, still smarting from the horror and trauma of the Fairview Park march some months earlier.

At an ad-hoc rally outside the GPO, Corkman Cathal Kerrigan, playwright Joni Crone and myself addressed an ecstatic crowd. Joni was then Ireland’s most public lesbian, having been the first woman to come out on public television when she announced it on the Late Late Show in 1980, and on this day she delivered a manifesto of liberation and rededicated the GPO – with all of its symbolism as the headquarters of Irish resistance to oppression – as the Gay Person’s Organisation.

All of the bright optimism and political fervour of those mid-80s parades came to a juddering halt in 1986. People were burnt out and emigrating in their thousands. In any case, there were more immediate concerns as AIDS rampaged through an already embattled community. My last notable Dublin Pride events of that decade were a condom picket outside the Vatican Embassy and a Kiss-In at Leinster House, neatly illustrating the combined concerns of the time: safer sex and decriminalisation.

Unsurprisingly, it fell to a younger generation of HIV/AIDS activists led by the fearless Izzy Kamikaze to reboot the Dublin Pride parade in 1992. Forty years later, Izzy laughs about how ad-hoc and homespun the entire affair was.

“We felt we had to do something, after being inspired by Belfast’s first Pride the previous year, but we weren’t even sure people would turn up!”

Emboldened by its success, the following year almost a thousand people sallied down Dame Street on 26 June 1993 to a rally in front of the Central Bank building. With extraordinarily good timing, the government had repealed the old anti-gay legislation two days earlier, prompting beloved street performer Thom McGinty, aka the 'Diceman', to do a strip tease on the steps of the bank. Free at last! We partied hard that afternoon and I’m not surprised that the bank decided to erect railings around the steps the following year!

Pride after decriminalisation

Decriminalisation undoubtedly signalled a shift not just in the fortunes of Dublin Pride but in how mainstream society embraced its sexual minorities. No longer criminals, it became possible to access statutory funding and corporate advertising in a way that would have been unthinkable in the 1970s and 1980s. Cultural and recreational pursuits, from theatre and cinema to sporting groups, blossomed under the new social dispensation offered by decriminalisation.

In the years that followed, and as more and more pieces of the legislative jigsaw fell into place and equality became something tangible, Pride became a big, celebratory family day out centred on the large space by the Dublin City Council building (then the offices of Dublin Corporation) on Wood Quay. By the time it outgrew its 4,000-plus grassy amphitheatre, people were complaining about the jettisoning of the children’s funfair to accommodate the crowds.

Those last rallies at Wood Quay were also focused on harnessing the visibility and collective voice of Irish LGBT people in getting marriage equality and gender recognition legislation over the line, as Ireland did so emphatically in 2015, when nearly two-thirds of the country voted in favour of repealing the ban on same sex marriage.

All-inclusive Pride

When the Dublin Pride parade rally moved to Merrion Square in 2012, it was impossible not to see the symbolism of reclaiming one of Dublin’s most beautiful public spaces after those fraught Pride events of the 1980s. The move also signalled a shift in the scale and ambition of the event, helped in no end by a more proactive city council keen to give full expression to notions of social inclusion and diversity.

And to the cynics who imagine that the embrace of the city council and corporate sector is nothing more than a shameless mining of the fabled Pink Euro, my generation is old enough to remember a time when we weren’t valued as consumers or at worst ignored, when we were refused service during the Pride pub zaps of the 1980s.

Gilbert Baker, the designer of the rainbow flag, sadly deceased, once said to me when we fell to critiquing the role of the corporate sector: “Being valued as a consumer is inherently liberating as we are no longer invisible! But the engagement of the corporate sector has to be on our terms.” (We were having lunch in a swanky Dublin restaurant at the time, paid for by a corporate sponsor!)

What Pride means to me

Writing in the Dublin Pride programme just before the pandemic took the parade off our capital’s streets, I observed that Pride can be so many things to different people. “It is at once a political protest at unfinished business, a street rave, a family day out, a chance to catch up with friends (and even ex-lovers). It is a necessary corrective to often drab street life and pervasive heteronormativity. It is a time to celebrate – come what may – our relationships and our families, both biological and logical.”

Progress in civil liberties and inclusion is rarely linear. We can introduce any number of laws and regulations but there’s still work to be done in eradicating lingering prejudice, fear and ignorance. This is when Dublin Pride reminds us of its enduring value. As the most visible element of LGBTQ+ Pride Week, I liken the parade to a contract between the LGBTQ+ community and the citizens of our city. Yes, of course, it’s a fabulous piece of street theatre – bold, colourful and occasionally transgressive. But it’s that one essential day of the year when we can all wonder at the distance we’ve travelled.

As that 80’s banner so presciently affirmed, LGBTQ+ liberation is your liberation. It is the story of a community finding its voice and asserting its rightful place at the centre of Irish society. But it is equally about that society at large finding its common humanity and a more refined and lasting sense of empathy towards minorities in its midst.

If for no other reason, it’s why I’ve missed only one Pride since they began and it’s why you’ll find me again at this year’s parade, marking its 40th anniversary and possibly teary at the fabulous queer spectacle I could only dream of as a stroppy nineteen-year-old in 1980, when roaming the streets in search of a pink riot.

At its heart, Dublin Pride is the ultimate midsummer festival with a big queer heart that the city has been crying out for since, well…forever. See you there!

Celebrate Dublin Pride 2025

From dance parties and film screenings to workshops and walking tours, discover 12 great events on for Dublin Pride 2025.